What if every community, regardless of size, type or place, could live self-securely in terms of energy, water and food, while producing no waste? How would this benefit society, or indeed, the entire planet? Terragon Environmental Technologies Inc. is giving the world the answer to these questions, now.

Terragon Environmental Technologies calls these communities ARCs (Autonomous Resilient Communities), and they arose from the idea of generating resources locally and eliminating all waste via two key technologies developed by Terragon: MAGS and WETT, along with the generation of renewable power.

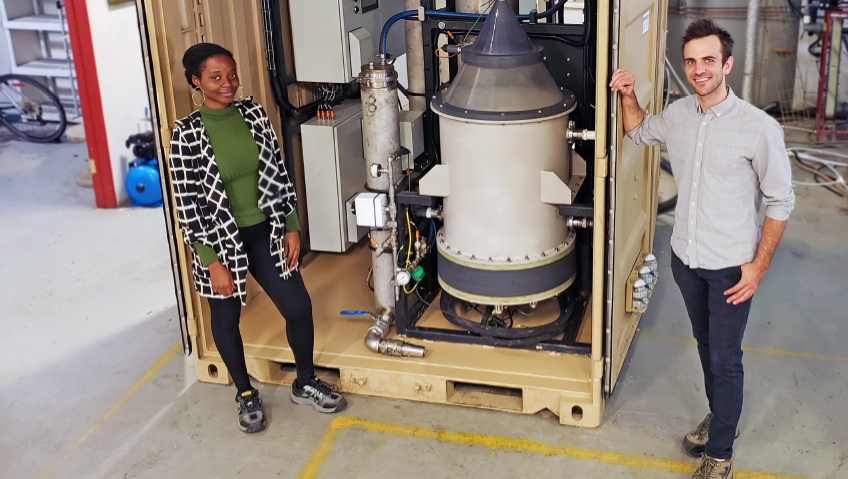

MAGS is a furnace to treat solid waste that can use anything as fuel. It converts solid waste into biochar and thermal energy through a gasification process, not by burning it. The gasification process produces a fuel called synthesis gas which is easily combusted in a combustion chamber, producing the energy required for the gasification process and excess thermal energy in the form of hot water which is recovered and used by the site. The exhaust gas is cleaned within the MAGS unit before being exhausted into the atmosphere. In short, by-products can be used to produce heat for any site or biochar for use in gardens and agriculture.

WETT is a water treatment system capable of producing clean water from various wastewater streams, including blackwater, greywater and oily water. An example of its use is the treatment of water from the laundry and shower and its reuse for laundry and toilet flushing. Just this simple activity would reduce water consumption in the home by 60 percent.

By using MAGS and WETT systems, an ARC can have heat recovery from combustible waste products or biomass, use the biochar as a soil amendment, and treat water for reuse and potability, allowing resources to be treated within the community and then repurposed to initiate another cycle.

Local resources

“We developed these technologies as part of an innovation cycle aimed at generating local resources,” says Tsantrizos. “When you look at the renewable energy field, it’s all about local energy generation. The idea of not importing petroleum products from other parts of the world, but using local resources like wind, sun, and biomass to generate energy that we need locally.”

Dedicated to developing appliances that enable small to medium habitats to treat their own waste locally without environmental damage, Terragon urges consumers to consider the concept of waste, how it becomes repurposed and its value in generating useful resources.

“You may ask why is this important?” says Terragon President Peter Tsantrizos. “The normal way we do things is based on an industrial grid; we work for industry, industry pays us, and then we use that money to buy what industry provides. This works pretty well in some ways, but it doesn’t provide the same level of services to all the remote communities.”

As the world becomes more damaged by practices for generating our own energy, water and food, remote communities are the first to feel the effects, he says, which created the concept that will allow these communities to develop a healthier and more sustainable way of living.

Need for change

How does the concept of “no waste” relate to the generation of energy, water and food security? Tsantrizos says this is where the misconceptions surrounding waste need to change.

“Waste is useless things we don’t need. We throw them out, and then we transfer them to some central processing facility. As the economy of the world evolves, we produce more waste, more stuff we don’t need, and we just transfer it to other people.”

Because of this, the waste management business is growing, but the amount of waste we generate per year is too. There’s an alternative to the idea of waste, however, that involves using resources locally to generate our primary resources, including energy, fertile soil and water.

“The way we actually think about waste management, the modern way, is recycling. It’s the main objective of our waste management effort. This has been presented to us as a viable alternative to generating waste. The problem is it doesn’t work.”

In reality, items that come from life forms like wood, paper, and food, all must in some way or another end up back in the earth. We can use these materials to make compost or biochar, produce energy, and eventually put them back in the earth to produce fertile soil for food.

Water is another example of waste being transferred in a beneficial way. Our homes use a one-pipe-in, one-pipe-out system. One type of water comes into our homes: potable water that’s used for everything. We drink it, wash our clothes, flush our toilets, give it to our plants, do laundry and wash floors with it.

Water for purpose

“This is quite damaging in the sense that all our drains are connected,” says Tsantrizos. “All the water we generate, even if it’s clean, goes to the same pipe exiting our home, the same pipe our toilets are connected to. So all the water from our home is now sewage and contains the effluence from our toilets and our laundry. It’s very difficult to convince people to reuse this water.”

The alternative is “water for purpose:” taking the water used for laundry and showers, cleaning it and using it for utilities like toilet flushing, laundry or washing floors. Kitchen and toilet water can be cleaned and used for irrigating and watering plants. By doing that, water consumption is reduced by about 80 percent, and basically eliminates the concept of waste, because there’s no wastewater from our homes.

“This relates the concepts of waste to the concept of energy, water and food security,” he says. “Effectively from our waste we can produce energy, fertile soil, and water. Those are the three elements needed to produce our food. Everything is interconnected in that very fundamental way. The more waste we generate, the more stuff we throw out, the more likely we suffer from energy and food insecurity.”

Beyond the technology and environmental aspect, these systems’ true importance is the impact on communities, says Tsantrizos.

“Communities need to have people depend on each other. You develop a community. Imagine a community where everyone is completely isolated from one another and basically looks to the industrial grid to provide everything. They go to the grocery store, they buy what they need, they go to the gas station, they open their tap, they get their water, and they have no interaction with their neighbour.”

This is where we’re heading in terms of the dominance of the industrial grid in our life, he says, while we’ve lost the ability to know our neighbours.

Living local

“I’ve lived in societies where things weren’t like this. One neighbour would produce fruits and one would produce grains and another would fish. There is a knowing within the community who is providing the primary resources. This creates an interdependence between people, which is fundamental to creating a sense of community.”

If these communities are healthier environmentally and socially and have better quality food, how do we get there?

“One thing that happened as a result of the COVID pandemic is we realized how important our social bubble was,” says Tsantrizos, “that small group of people we maintain contact with. COVID also disrupted our supply chain, so a lot of food that was coming from other parts of the world, and our energy, all these things were now problematic. That was an indicator of how beneficial generating local resources is, and how beneficial not spreading the disease by having a locally based economy can be.”

This is where the government comes in, he says. The Government of Canada has made it clear it wants to build a clean-tech economy, transforming the way we live, the way we do business, and basically changing our entire core infrastructure.

Building Back Better, for instance, is a government initiative developed to invest between $70 billion and $100 billion over the next three years in ways that will help Canada move out of recession toward an economy that is greener and more innovative, inclusive, and competitive.

The government has already done some interesting things with Innovative Solutions Canada, creating a number of challenges that develop specific technology related to living with COVID, or energy or waste management. These challenges were essentially designed to create a technological infrastructure needed to create communities.

Contributing to communities

“Imagine doing this with one of our northern communities,” says Tsantrizos. “We create a challenge where we ask Canadian companies to contribute ideas and technologies: food, water and energy, and zero waste. Consortiums could form, and could demonstrate this concept in some of our communities. Then we could actually roll this out across the country and supply to all the communities.”

But problems in communities are not just technological, he adds: there’s also human capacity.

“We don’t necessarily have the skills, especially in remote communities to operate and maintain and do these things. We talk about local food production; these communities are basically hunters and fishermen. They need new skills. There’s a requirement beyond the challenge of identifying the most suitable technologies. Another challenge is creating capacity within these communities.”

Very often these communities have no local jobs available, and the most talented are forced to leave and seek their fortunes elsewhere, or they end up working an industrial activity.

“It doesn’t give them any kind of motivation to succeed. In a traditional community, where the community generated resources, there were jobs for everybody. Everyone could grow food or generate energy or manage water.”

It all begins with education, says Tsantrizos. We have to restructure our education system that right now entirely focuses only on doing things like getting a job.

“We get no training at all about how to grow a tomato, or change a diaper, all the critical things we need to know. These skills are undervalued in our society. Being a stay-at-home parent is probably the most important thing any human can do. It’s the joy you get from raising your own children or growing your own food. There’s a kind of euphoria that comes from those things.”

Physical health and more

The issue’s not just about physical health, it’s about emotional and social health, too, Tsantrizos stresses. Education doesn’t just mean a school education: It’s teaching young children experiences like fishing and contributing to the family in a meaningful way. “We deprive them of that excitement when we lock them up in boxes and schools and then teach them how to go get a job.”

Right now we also spend very little money on our primary resources, he says, and instead spend most on things we may not need.

“You’re probably spending more money on social media than on food you need to survive,” he says. “When we start looking at the cheapest way to get food and get energy, we actually devalue them and we create value for other things like going on a cruise vacation. This shift must happen and it must happen on the education side, and in how we value the things we consume.”

At the grocery store you’ll find locally grown tomatoes alongside imported ones. Locally grown tomatoes will taste better, but of course they’re more expensive. While you can produce tomatoes cheaper in Mexico, they aren’t the same tomato you’ll grow locally, plus you’re not contributing to the health of the society where you’re living.

Tsantrizos wonders why growing food is so inappropriately rewarded. Why do we not value the person going out and working the field to provide food so we can actually create Canadian jobs? There’s value in having your own resources, he says, and there’s value in protecting your local environment.

“If you look at success stories, all of them are local stories of people that manage to regenerate the farm,” he says. “It’s always stories of managing what they have and protecting the land and the water they live from. We need to enhance these stories. We need to make local heroes of the people and not devalue them.”

Thriving together

Ultimately, Tsantrizos says society must shift its basic understanding of what happiness is, and how to achieve it. And it’s not by consuming “things.” He adds, “Everyone talks about growing the economy as being the way we succeed, but they’re really talking about growing the consumer economy, because we live in a consumer economy. The idea is get more money, and consume more stuff and that should make you happy.”

What’s more, he says, the problem is that happiness is almost never derived from consumption. Happiness is a relationship-based emotion that comes from seeing your friend smile, or the relationship you have with your spouse or your children. “These are the sources of happiness – our health too. Not when we buy a car.”

In summary, a society focused on health and happiness is a better society than one focused on growth of the consumer economy.

“Ultimately people talk about destroying the planet. We’re not destroying the planet. The planet is far more resilient than we are. We’re just destroying the conditions that the planet has maintained all these years and that have allowed our societies to grow. So we’re damaging our societies. We’re damaging ourselves.”

But there’s still time to change all of that for the better.

“Whether it’s a military base or remote community or a city block, all of us can benefit from the idea of becoming more resilient and more autonomous with potential primary resources and also with our waste,” he says, “and Canada has a great opportunity to lead this transformation globally.”